In the long-ago time when Edo was founded, there was a stone carver called Ishida Tetsuo. He came from a long line of quarrymen who lived on the Boso Peninsula, where stone was pulled from the mountains and turned into building blocks for the new capital city.

He apprenticed with his father, who had left the quarries and made his living chiseling stone monuments for cemeteries. It was clear from a young age that Tetsuo inherited his father’s talent for stone carving. As a child, he shaped scraps of rock into little animals. Given his own set of tools at age 11, he apprenticed with and quickly surpassed his father, moving from tablets to lanterns to temple sculptures. He was not only a craftsman but an artist.

Ishida Tetsuo’s skill was great and his prospects were bright. His creative vision invigorated the family business and he and his father were sought after by all the local temples and wealthy families. Tetsuo was always busy. He had no time to look for a wife and start a family as his friends did, but he was happy with his stones. His sculptures were his children and he enjoyed seeing them in the villages.

On his 20th birthday, February 6th, he received a letter addressed to him at the workshop. Inside was a request for a commission from a temple far away in Shikoku. The temple priest wanted a bird carved as tall as a man, as wide as a bull, and with a tail split like a serpent’s tongue. Many particulars were specified – the shape of the eyes, the number of feathers in each wing, and even the joints of the clawed feet. The sculpture was to be started immediately and the last stroke of the chisel to be made precisely on the 108th bell of the new year.

It was unusual for a commission to be so elaborate. Typically his patrons requested a certain shape or an animal and Tetsuo took on the creative side himself. But this commission was interesting and lucrative, too, so he wrote back to them to say that he would begin right away.

It was not an easy task. The bird required four stones to fit together for the body, wings, and tail. The balance had to be perfect. It took many months just to shape the stones and fit them. The detail carving was intricate and as the end of the year approached and the deadline loomed, Tetsuo was worried that he would fail to make the last stroke before the appointed time. He worked frantically for weeks leading up to the last day of the year.

Late in the evening on December 31st, his parents went to the temple next door to offer their prayers to the gods and receive blessings for the coming year, but Tetsuo stayed in the workshop rushing to complete the final feathers on the sculpture.

MIdnight approached and the priests chanted. He could hear the crackle of flames as last year’s amulets burned. And then the temple bell started ringing in the new year. Bong. Bong. Bong. Slow and steady peals rang out into the night as each priest in turn struck the bell. Then the community leaders continued the long peal of 108 mortal sins. Testuo counted each one as he worked in a race against time. Finally, 107…Bong. Tetsuo chipped away one last fragment of feather. 108…Bong. He set his tool down, pleased that he had observed the deadline so precisely.

Bong. Another bell. 109th? No…it came not from the temple next door, but from the air next to Tetsuo’s ear. A ghostly version of the temple’s bell. He shook his head and left the workshop to join his parents and see in the new year.

After the holiday, he spent some months polishing the enormous bird carving, but not a single additional cut was made. The bird was as tall as a man, as wide as a bull, and with a tail split like a serpent’s tongue. Each wing had 108 embellished feathers. The eyes were almond-shaped. The long tail split into two – with feathers fanning upwards and some reaching down towards the earth. It was the masterwork of a youthful craftsman. He was proud to send it off to the temple in Shikoku. They received it and he was paid. He didn’t hear from them again.

Ishida Tetsuo moved on to other projects and his reputation grew. He took commissions from temples in Tokyo, from rich landowners all over the country, and eventually from the Emperor himself. He found a wife and she bore him sons. They lived a happy life near the bay.

His sons came to apprentice with him, as he had studied with his father. While they did not have the natural artistry of Tetsuo, they were skilled and able to execute their father’s designs and take on the simpler work.

Time passed by in the blink of an eye. Tetsuo’s sons married and had children of their own who grew up to have children, too. The younger generations handled most of the business as Testuo grew older. But he still enjoyed taking on the most creative and artistic projects.

On his 60th birthday, a letter arrived from the same Shikoku temple that had commissioned the bird forty years earlier. It was a request for a stone lantern. Tetsuo considered this as a special gift for his 60th birthday and took the commission personally.

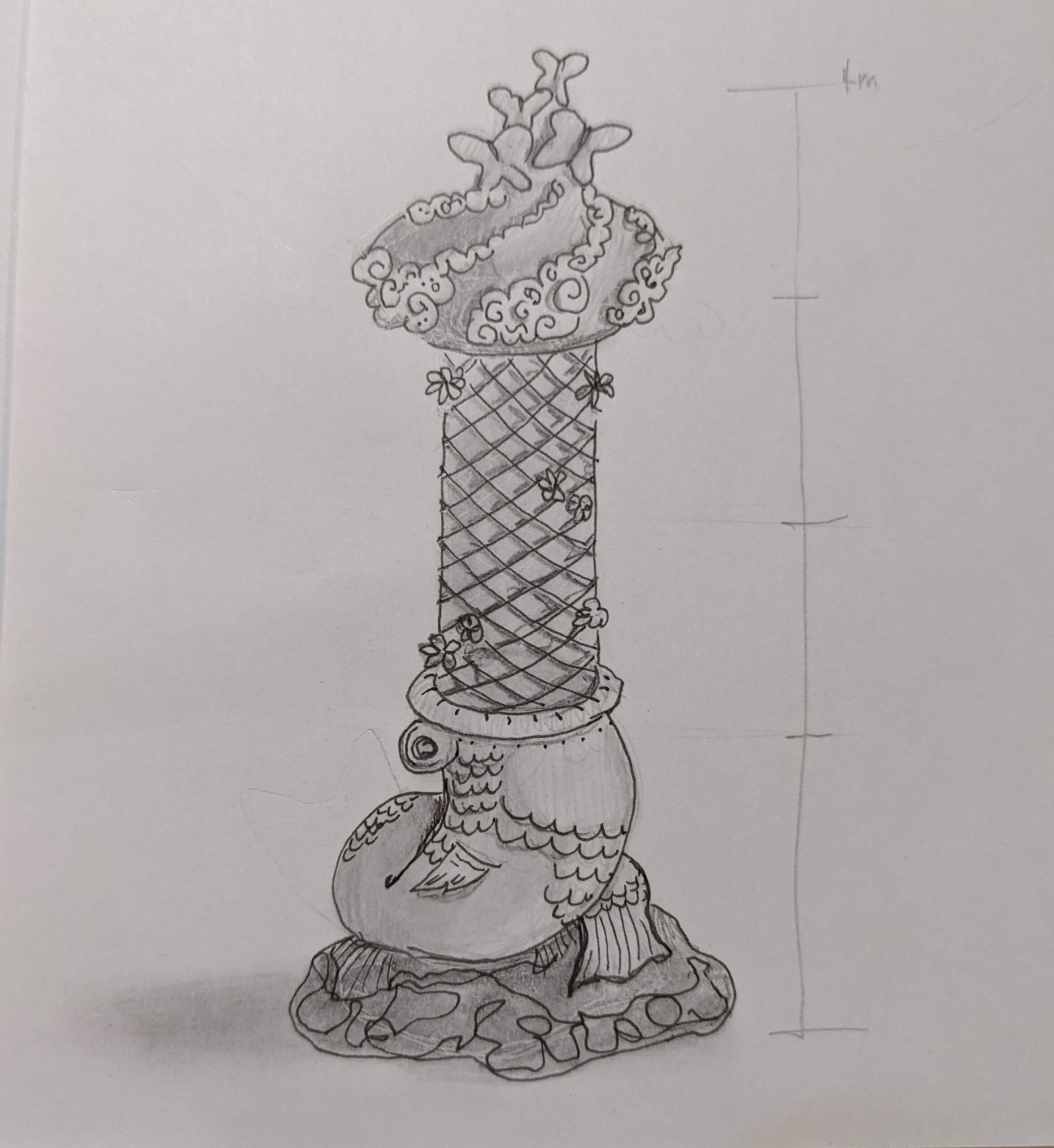

Again, it was a challenging order. The lantern’s size was massive, with unusual proportions and decoration. The finished piece was to stand over four meters tall, with a slim lattice work shade festooned with blossoms. Atop the lantern, a finial of butterflies. The base of the lantern would not be the usual octagonal plinth, but a carp, curving up to grab the lantern in its mouth. As soon as he read the description, the final form of the work bloomed in his mind. It would truly be his life’s masterpiece.

This commission paid handsomely and Tetsuo dreamed of how he would use the money. Perhaps a trip with his wife. Or an addition to the house. There was some land adjacent to the workshop that he could acquire and expand into.

But there was a catch to this commission and a reason for its generous payment. As with the bird, the work needed to be completed on a strict deadline. The last stroke of the chisel was to be made before the end of the final dance of the Obon festival in late July.

It wasn’t much time, so Testuo got to work. He selected the stone, drew the sketches and started to carve as the sakura bloomed. Every day, Tetsuo rose with the sun and worked until sunset. His intensity chased his sons from the workshop, and they set up a new shop on the adjacent land with money loaned by their father.

As spring gave way to the rainy season, the lantern took shape. The latticed section bloomed with flowers from all four seasons. The carp’s mouth curved around the lattice and held it tight. Its tail gripped a rough hewn stone as if it had leapt onto a riverbank.

The heat of summer weighed down on the coastal town as Testuo began carving the top of the lantern and the finial. The cap was edged in tiny clouds that spiraled up towards the butterflies.

But the butterflies proved more challenging than expected. A few days before the festival, the finial cracked, leaving Tetsuo holding one butterfly in his hand as the other three fluttered to the ground and shattered. He would have to carve them again. What had taken weeks would have to be completed in days. He worked around the clock.

The day of the festival dawned and Tetsuo listened to the drums beating as his family and neighbors went to the temple to dance with the ancestors. The air was heavy with the smell of incense. Food stalls lined the path leading to the temple and children delighted in games with small prizes.

Bamboo flutes trilled and the dancing started. Tetsuo was more than halfway finished, but the details on the butterflies were not complete. This decorative work required concentration and it was hard to focus with the festival in full swing next door. But he persevered, knowing his strange deadline was just a few dances away. Maybe he’d manage.

He blocked the distractions from his mind and chipped away. But as the last drumbeat of Tanko Bushi faded away, he was tracing patterns onto the wings of the butterflies. He heaved a sigh. He could stop now, but the butterflies were still too plain. He decided that he must miss the deadline, so that his work would be perfect. There was no other way.

Bong. At that moment, mixed into the burble of revelers leaving the temple, he heard a bell. Not from the temple, but in his own ear. The memory of the 109th bell from years ago sprung to his mind but he shook his head and lifted his hammer to take the next stroke. His hand, always steady and sure, trembled. He swung the hammer with extra energy to make up for the tremor. The chisel slipped as the hammer came down.

Two fingers dropped to the floor of the workshop. Tetsuo shouted in pain and fear, drawing the attention of neighbors still leaving the Bon festival.

Ishida Tetsuo took to his bed for weeks, refusing to go to the workshop even after he had learned to manage daily life without his fingers. His sons finished the lantern. They filed and polished the stones, but carved nothing more. The butterflies remained rough hewn.

A letter from the temple arrived, directing the lantern to be delivered by ship from the Tateyama port. His elder son brought the letter to Tetsuo, who was languishing in bed.

Tetsuo decided to accompany the work in order to apologise for the delay. He was also curious to see the bird that he had carved so many years ago.

The open sea did not charm him. Though he had always lived on Tokyo Bay and his neighbors were mainly fishermen, Tetsuo had only been on the water once. He was a man of earth, not sea. The journey to Shikoku took three days and nights. Tetsuo hung a hammock near the lantern and slept in the shadow of his work. He ate with the crew and otherwise kept to himself until the ship docked and the lantern was unloaded.

Arriving at the temple, he presented the lantern to the priest with all due consideration, then wandered the sacred grounds to find the bird he had carved.

It sat to the side of the pagoda, on a path leading towards a sacred tree. Tall as a man, wide as a bull, with a tail as long as a serpent, it perched on a tall marble plinth. But the bird could be seen only from below. None of the features that had been commissioned – 108 feathers on each wing, the split tail, the almond shaped eyes- could be seen at all. The clawed feet with their special joints were at eye level but all the rest was invisible to the pilgrims who visited the temple.

Tetsuo grew angry. This was not how he expected the statue to be shown; he would have done things much differently if he had known it would be seen only from below.

He turned away from his creation, bitterly regretting his decision to come to see it. He vowed never to take another commission from this temple and to bar his sons from doing so, too.

Bong. As he stepped away from the bird, he heard a bell, followed by a metallic clunk hitting the gravel path behind him. He turned to see a brass chisel, in the shape of the bird’s split tail, on the ground. He reached for the chisel, a true prize, and as his hand touched it, he felt an electric shock and his heart turned to stone.

Years later, when their grief had worn down with time and their father’s reputation had grown even in his absence, his sons petitioned the town of Tateyama to erect a monument to Ishida Tetsuo. They designed it as a rough hewn monolith with chisel marks down two sides revealing a smooth marble column. Atop the column, a weathervane swings in the wind, an oversized brass chisel in the shape of the bird’s tail.

The monument stands in the park of Tateyama Caste to this day. When the wind blows from Shikoku, it is said that uncanny things happen.

This story was inspired during a picnic at Shiodome Park, in the shadow of Tateyama Castle. We sat near an intriguing sculpture titled “Light, Wind, Dreams” that begged to be explained. So while we feasted, I improvised the bones of this story. I liked it enough to flesh it out, turning it into something akin to a summer ghost story just in time for Obon.